I drafted this piece on Saturday, March 25, 2017, when no one knew if or how much money Governor Larry Hogan would “give” to Baltimore City Public Schools in his second supplemental budget. My child’s school was facing a 20 percent cut to our budget. I updated it on the 27th, when Hogan announced his add for City Schools. Now it looks like my child’s school budget will be cut 5 percent. I’ll just leave this here. I have been told it deserves to be shared.

On March 27, the governor of Maryland announced a plan to allocate to Baltimore City Public Schools an additional $23.7 million, which represents a small fraction of a multi-million dollar budget gap. For advocates like me, a big trick of fighting for funding has been figuring out what to show to illustrate projected losses: a dollar sign, a percentage, an image of a classroom with 25 students next to the same one with 40?

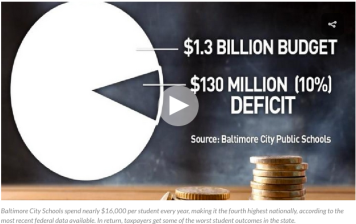

The figure Baltimore City Public Schools CEO Sonja Santelises presented, and then leaders of the Downtown Baltimore Family Alliance ran with, and now Fox45 News is promoting to particularly misleading effect, is $130 million. That is the amount – rounded up by one to the nearest 10 – of the structural deficit that City Schools lacks the revenue to fill this year, and next year, and the year after that.  Divided by the average teacher salary, it signifies more than 1,000 positions, rounded down by hundreds. In a panic that elided the need for a three-year fix, DBFA branded a campaign #releasethe130. In a simple pie chart, Fox45 reduced the 130 to a sliver – 10 percent – of the school system’s $1.3 billion budget.

Divided by the average teacher salary, it signifies more than 1,000 positions, rounded down by hundreds. In a panic that elided the need for a three-year fix, DBFA branded a campaign #releasethe130. In a simple pie chart, Fox45 reduced the 130 to a sliver – 10 percent – of the school system’s $1.3 billion budget.

Fox45’s coverage hands rural Marylanders ammunition to fight spending on the big city. “Baltimore City Schools spend nearly $16,000 per student every year, making it the fourth highest nationally, according to the most recent federal data available,” Fox asserts. “In return, taxpayers get some of the worst student outcomes in the state.” Countless “school reform” pushers and county politicians have used the same talking point, neglecting to mention that Baltimore has the highest rate of concentrated poverty, the highest percentage of students with special needs, the highest number of lead poisoned children. Their point: Money is wasted on Baltimore.

Also lost in the discussion of $130 million are the figures by which Baltimore City Public Schools have been underfunded for years. City Schools would have no deficit at all if the state had not cut the inflation adjustment nine years ago. If not for a decade of flat funding and rising costs, we would have at least $290 million more revenue this year, from the state alone. That does make $130 million seem small, not to mention $23.7 million.

Moreover, a state study released in late 2016 found that Baltimore City Public Schools would need an additional $350 million from the state to meet a funding level adequate to enable students to meet state standards. In three years, when the commission working on a revised state funding formula arrives at one that is fair and equitable, one can only hope for the sake of all students in Maryland that the governor fully funds it.

What no one in the media has looked at is what happens to the 10 percent district-level deficit when you distribute it across schools. It balloons.

My child goes to a Pre-K–Grade 8 public school in Baltimore City with more than 700 other students. The school touts low teacher turnover, a middle school Ingenuity program, a recently won E-GATE certification for gifted and advanced learning instruction, partnerships with MICA for arts instruction and McDonogh School for middle grades enrichment. It offers vocal and instrumental music, art, Spanish, fitness, and library time. After-school clubs include STEM, dance, musical theatre, French, Italian and Spanish.

If the district’s 10 percent deficit does not close, our school will lose up to 20 percent of our budget. One fifth. It will be as if we have lost funding for 140 students.

When that cut was announced in late February, “school choice” came to mean deciding whether to keep the half-time librarian. It meant weighing whether to eliminate the Gifted and Advanced Learning position or the vocal music position in exchange for keeping two kindergarten classrooms rather than squeeze them into one. It meant taking a hard look at whether the PTO at a school that receives the highest level of Title I funding possible, because nearly 9 of 10 students’ families qualify for nutrition assistance, has pockets deep enough to purchase a year’s worth of printer paper and fill the tuition gap for a sixth grade outdoor education program that will now take a lot more than T-shirt boosters and church-basement chili dinners to fund.

If that 10 percent gap is not filled, my school alone stands to lose six teachers and five staff. We will lose the Playworks coaches who elevate the mood at school on and off the playground. The school will make do, but it will not be the same.

That is what will happen to my child’s school as a consequence of this sudden budget crisis, a crisis the CEO says she did not see coming. But fighting that doesn’t stop me from thinking about what happens when whole school districts are inadequately funded. Many families with means leave. The few that stay invest in our own children’s schools. Buildings crumble. What is left are majority black and brown, minority-run, urban Democratic districts from which white Republican governors feel fine withholding tax dollars. And amidst the politics and the backroom dealing and the accusations of bloat and mismanagement, poor children don’t learn how to read.

The debate on this over the years has centered on whether the cause of “student failure” is teachers – and their unions – or poverty. The reformers say, “Hold teachers accountable.” The teachers say, “We can’t correct for poverty.” The reformers say the highest spending per pupil happens in poor performing schools, ignoring again and again that the highest spending goes to students with the highest need – students who need to learn English, or need speech and occupational therapy, or need a paid adult to accompany them throughout each school day. Some teachers unions inexplicably agree to have their pay correlated to student test scores.

All this — the underfunded school districts, the concentrated poverty, the race baiting politics, the crippling of teachers unions, the ignored needs, the batteries of tests — has forced a crisis of low student achievement. When students can’t reach “proficiency,” agenda-driven nonprofit groups peddle solutions to politicians eager for a fix that promises to preserve the racial status quo and please everyone — urbanite and county bumpkin alike. Those solutions are vouchers to private and religious schools, charter school expansion, “turnaround districts” that wipe out traditional public schools. Governors impose “accountability measures” for districts in exchange for state funding, even if that funding is not only a pittance but decades past due.

This year in Baltimore, as parents have been rallying to #releasethe130 and #fixthegap, Governor Hogan’s staff and appointed school board members have been rallying, too. It’s all in the open. They proposed legislation to create a separate, governor-appointed chartering authority for Maryland that would override local control, turn charter teacher unionization into a “right to work” opt-in situation, and undo efforts toward fair and equitable charter and traditional school funding. The governor and state board of education are aggressively resisting a bill that would limit test scores to just over half of student proficiency measures, gunning for three quarters. They have no interest in improving, let alone sustaining, a system of schooling that is publicly managed and run. In fact, Governor Hogan doubled funding for private and religious school vouchers as he ran out the clock on deciding to support the 11 Maryland school districts, including Baltimore City, that lost state revenue because they lost enrollment.

The media is full of numbers: $130 million, $290 million, $1.3 billion, $16,000. So is my head: One-fifth cut, six teachers gone, 9 of 10 classmates in poverty, $10,000 in printer paper for a whole school year. In the end, though, it all comes down to one individual. I don’t mean the governor. And I don’t mean my kid. I mean one whole child. No one should tolerate for a second the notion that Maryland’s budget – whatever Governor Hogan might say – funds a student in a single public school as if he or she equates to a fraction of a person. We all have a responsibility to keep our children whole.

Leave a comment